|

=

We'd seen it on the map and we'd passed the prominent sign 450 kms east of Norseman before, but the Eyre Bird Observatory remained unexplored. This time its secrets would be revealed. "This won't take long", I said as our Ford Explorer motored effortlessly down the wide Telstra access road that adjoins the Eyre Highway just east of Cocklebiddy, WA. "You could land a jumbo on this road", observed Phil, committing a mild exaggeration. Perhaps just a 737 then? This ample track, a good 50 metres wide in places, went just as far as the huge microwave tower that was about 10 kilometres south of the tarmac, then it closed in. Right in! So much so that leaves and branches wanted to 'high-five' us as we passed gingerly by. We came to a little cul-de-sac at the end of what was now just a trail. Miffed, we were about to turn around when Phil noticed another trail disappearing over the edge of a nearby precipice. We parked the Explorer and alighted for a first hand inspection. Whoa! I could easily see why most novice adventurers passed up on the Eyre Bird Observatory. The narrow, rocky little trail plummeted down the escarpment at a dizzying angle. A murmur, a shared glance and... yep!

Rocks turned to sand as we wound our way through twisty tracks between robust little mallee shrubs. A thoughtful sign reminded us to let our tyre pressures down, which we duly did. The fine dry sand, of varying depths, would clutch at us trying to drag us down, and then with the revs up, spit us out again. This slow ordeal went on for nearly twenty kilometres, taking us almost an hour.

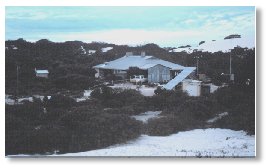

Finally the dense bush cleared a little and we could make out the shape of a tin roof with an old sandstone chimney attached. This was the former Eyre telegraph station, built in 1897 to replace the original weatherboard cottage, and abandoned just thirty years later when the line moved north. For fifty years the empty station stood its ground, a memorial to both bravery and foolishness, until it was resurrected by the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union, now Birds Australia. Today it's used as lodging for BA staff and volunteers, with a spare room for overnighters wishing to stay.

James, who has the paid position and a double-time job, is occupied with the daily running of the place. Apart from maintaining the small fleet of 4WDs, the power supply, the tracks and the vermin traps, he submits weather reports to Perth three times a day. Beach wash rubbish is also logged. A prime function for the pair is to conduct the numerous bird and wildlife counts, often as many as five separate surveys each month. James, a keen photographer, also shoots and develops his own film, so we were treated to an impromptu showing before we took some of our own. Naturally his favourite subject is birds, of which there is an abundance. Major Mitchells, silver eyes, purple-gaped honeyeaters and spotted pardalotes to name just few. To see these very special feathered creatures anywhere outside a zoo or a book is quite a treat, and that's the way the Brownlies intend to keep it. Feral animals can still be a problem even in a remote place like Eyre. Cats are quickly dispatched, as are the scourge starlings. The sun was low in the sky when we bid Eyre a reluctant farewell. I packed a few of Debbie's greeting cards into my bag before we set off on the return trip, and by the time we extricated ourselves from the dark undergrowth and found our way back to the highway, the stars and our headlights were the only sources of light. Postscript: James and Debbie's term expires at the end of June 1998. Debbie intends to return to full-time painting. James will work at the nearby Cocklebiddy Roadhouse until they decide what to do next. Related pages: Eyre Bird Observatory || Across the Nullarbor Download Map (PDF 60Kb) All content, unless noted otherwise, is copyright to the author and may not be reproduced or mirrored without prior express consent in writing. The author is duty-bound to prosecute unauthorised use of material from this site and will do so without hesitation. Prior permission is not required to link or reference material from this site, although the author appreciates notification. |

Postcard From Eyre

Postcard From Eyre  We put the big Ford into low-low gear and inched slowly down into the scrubby valley below. Easy does it! At the bottom we wondered what all the fuss was about, although getting back up was still going to be exciting.

We put the big Ford into low-low gear and inched slowly down into the scrubby valley below. Easy does it! At the bottom we wondered what all the fuss was about, although getting back up was still going to be exciting. Occasionally we'd see the old overland telegraph poles, some lying down amid a tangle of wire, others still defiantly erect, as we traced parts of the old route. The line is long gone. It was moved up along railway line during the 1920s because of constantly shifting sand that would often bury and break the fragile wires.

Occasionally we'd see the old overland telegraph poles, some lying down amid a tangle of wire, others still defiantly erect, as we traced parts of the old route. The line is long gone. It was moved up along railway line during the 1920s because of constantly shifting sand that would often bury and break the fragile wires.

James handles most eradication himself, but occasionally has to call in hired guns when the little black interlopers outnumber him.

James handles most eradication himself, but occasionally has to call in hired guns when the little black interlopers outnumber him.